The Truth About “Clean Eating” (and What Actually Matters)

Key Takeaway: “Clean eating” sounds healthy, but it’s actually a made-up term with no real definition that can make eating way more stressful than it needs to be. What actually matters for your health is way simpler—and more flexible—than Instagram would have you believe.

Your friend posts a photo of her “clean” breakfast bowl with seventeen different superfoods, while you’re eating toast with peanut butter and feeling like you’re failing at life. Sound familiar?

Here’s what nobody talks about: “clean eating” isn’t based on science. It’s a marketing term that’s created more confusion and food guilt than actual health benefits. And the irony? The foods that get labeled as “dirty” or “unclean” are often perfectly nutritious and can be part of a healthy diet.

The real truth about eating well is both simpler and more flexible than the clean eating crowd wants you to believe. You don’t need to avoid entire food groups, spend a fortune on specialty ingredients, or feel guilty about eating a sandwich made with regular bread.

Where “Clean Eating” Actually Came From

Let’s start with some history, because understanding where this whole thing began helps explain why it’s so confusing now.

“Clean eating” started in the bodybuilding world back in the 1990s. It was a very specific approach—high protein, low carbs, minimal processed foods—designed to help bodybuilders build muscle and cut fat for competitions. It wasn’t about general health; it was about achieving a very particular body composition for a very specific purpose.

Then something interesting happened. The term got picked up by wellness influencers and food bloggers in the 2000s, and suddenly it meant something completely different. Now it was about “natural” foods, avoiding chemicals, and eating only foods with short ingredient lists. The definition kept shifting and expanding until it became this vague concept that could mean almost anything.

The problem: There’s still no official definition of “clean eating.” Ask ten different wellness influencers what it means, and you’ll get ten different answers. Some say it’s about avoiding processed foods entirely. Others focus on organic produce. Some eliminate entire food groups like grains or dairy. It’s basically a choose-your-own-adventure approach to nutrition, which isn’t exactly helpful when you’re trying to figure out what to eat for dinner.

The Myths That Need to Go

Let’s tackle the biggest misconceptions that make eating way more complicated than it needs to be.

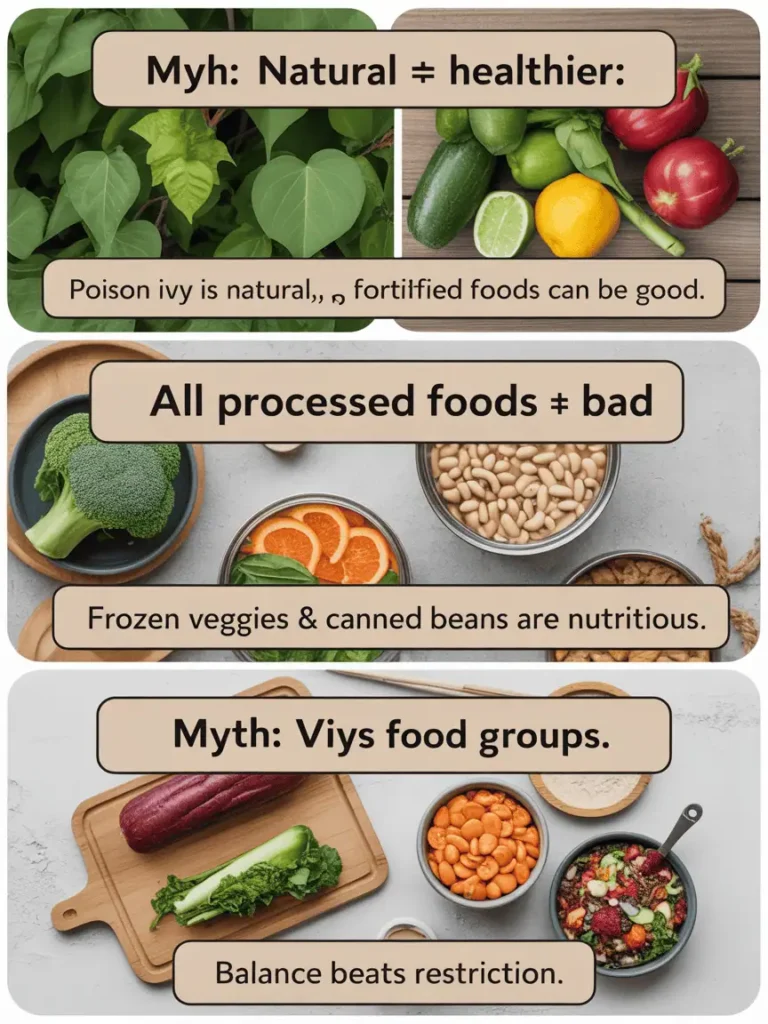

Myth 1: “Natural” Always Means Healthier

This is probably the most persistent myth in the clean eating world. The idea is that if something occurs in nature, it must be good for you, and if it’s been processed or has additives, it must be bad.

The reality: Poison ivy is natural. So are deadly mushrooms. Meanwhile, pasteurized milk (which is processed) is safer than raw milk. Fortified cereals (which have added vitamins) can help prevent nutrient deficiencies. Some food additives are there for safety—like preservatives that prevent dangerous bacteria from growing.

Real-world example: I used to avoid anything with more than five ingredients, thinking shorter lists meant healthier food. Then I realized that a homemade trail mix with nuts, seeds, dried fruit, dark chocolate, and a pinch of sea salt has five ingredients and is way more nutritious than a bag of pork rinds, which has three.

Myth 2: All Processed Foods Are Bad

This one drives registered dietitians crazy, and for good reason. The term “processed” covers everything from pre-washed spinach to frozen vegetables to canned beans—all of which can be incredibly nutritious and convenient.

The nuance that matters: There’s a difference between minimally processed foods (like frozen vegetables or canned beans) and ultra-processed foods (like chips or sugary cereals). The first category includes some of the most nutritious, affordable, and convenient foods you can buy. The second category is what you might want to limit—but even then, having some occasionally isn’t going to derail your health.

Practical approach: Instead of avoiding all processed foods, focus on limiting ultra-processed ones that are high in added sugars, sodium, and unhealthy fats. But don’t stress about eating canned tomatoes, frozen berries, or whole grain bread just because they’ve been processed.

Myth 3: You Need to Avoid Entire Food Groups

Clean eating often involves eliminating whole categories of food—grains, dairy, anything with gluten—without any medical reason to do so.

The science: Unless you have a specific medical condition like celiac disease or lactose intolerance, there’s no evidence that avoiding entire food groups improves health. In fact, it can make it harder to get all the nutrients you need and can lead to an unnecessarily restrictive relationship with food.

The mental health angle: When you label entire food groups as “bad” or “unclean,” you’re setting yourself up for guilt and anxiety around eating. Food becomes stressful instead of nourishing, which isn’t exactly a recipe for long-term health.

What Actually Matters for Your Health

Now that we’ve cleared up what doesn’t matter as much as you think, let’s talk about what the science actually shows makes a difference for your health.

Focus on Patterns, Not Individual Foods

The biggest shift in nutrition science over the past decade has been moving away from focusing on individual nutrients or foods and looking at overall eating patterns instead.

What this means: It’s not about whether you eat white rice or brown rice for lunch. It’s about whether your overall eating pattern includes a variety of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats most of the time.

The 80/20 reality: Eating nutritious foods about 80% of the time and enjoying treats or less nutritious options 20% of the time is not only fine—it’s actually more sustainable than trying to eat “perfectly” all the time.

The Big Four That Actually Impact Health

Based on decades of research, here are the four dietary factors that have the strongest evidence for affecting your health:

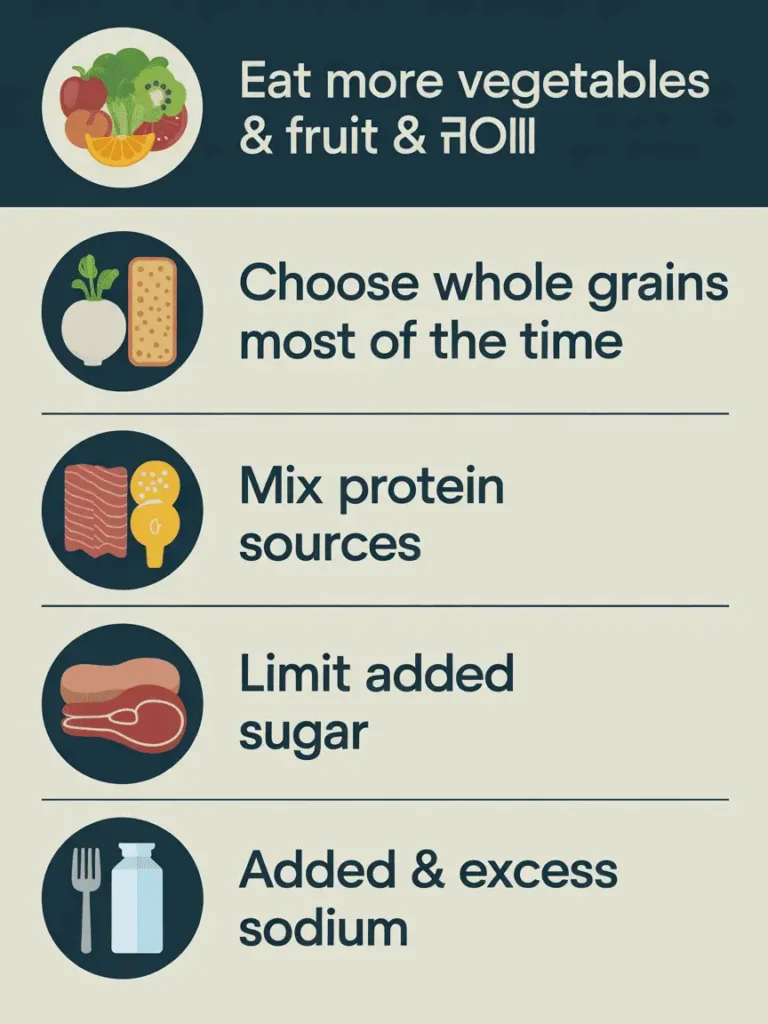

1. Eat more vegetables and fruits

This is the most consistent finding in nutrition research. People who eat more produce have lower rates of heart disease, certain cancers, and other chronic diseases. It doesn’t matter if they’re fresh, frozen, or canned. It doesn’t matter if they’re organic or conventional. What matters is eating them regularly.

2. Choose whole grains over refined grains most of the time

Whole grains provide more fiber, vitamins, and minerals than refined grains. This doesn’t mean you can never eat white bread or regular pasta, but making whole grains your default choice most of the time is beneficial.

3. Include a variety of protein sources

Your body needs protein for muscle maintenance, immune function, and dozens of other processes. It doesn’t care if that protein comes from chicken, beans, eggs, or tofu. Variety is actually beneficial because different protein sources provide different nutrients.

4. Limit added sugars and excess sodium

This is where some processing does matter. Foods with lots of added sugars or sodium can contribute to health problems when they make up a large portion of your diet. But again, it’s about the overall pattern, not individual foods or meals.

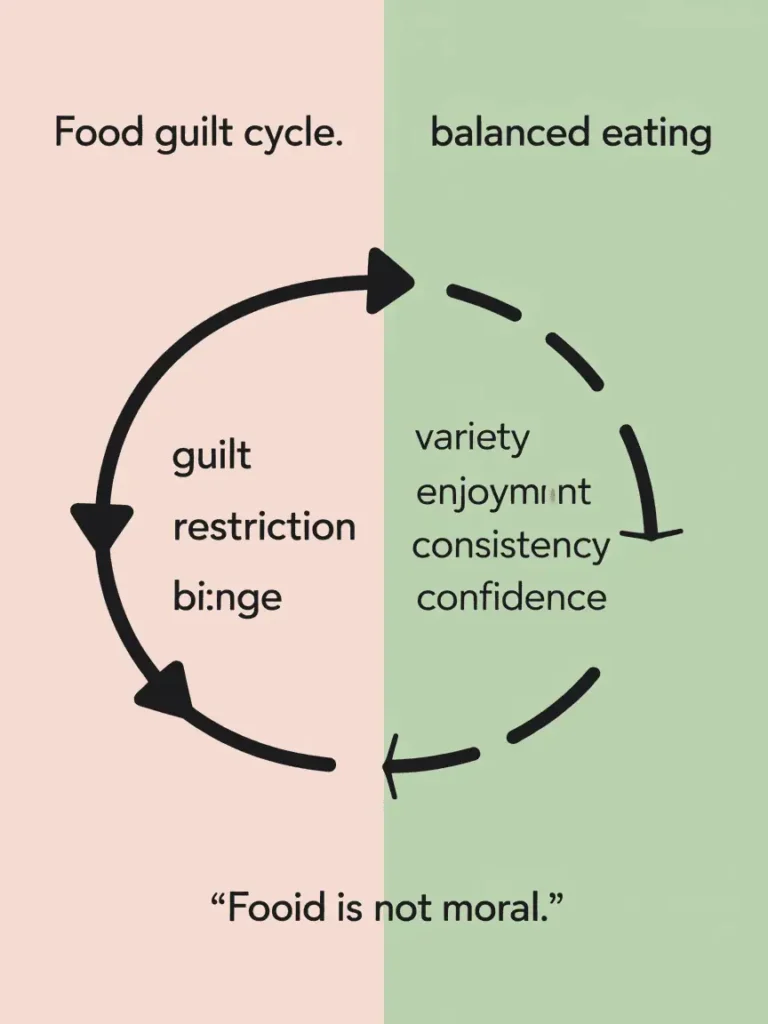

The Flexibility Factor

Here’s something the clean eating movement gets wrong: rigid rules don’t work for most people long-term. Life happens. You travel, you get busy, you want to enjoy a meal with friends without analyzing every ingredient.

What works better: Having flexible guidelines that you can adapt to different situations. Maybe you usually choose whole grain bread, but you don’t stress about it when you’re at a restaurant. Maybe you eat plenty of vegetables most days, but you don’t feel guilty if you have pizza on Friday night.

The research backs this up: Studies show that people who have a flexible approach to healthy eating are more likely to maintain their habits long-term and have better psychological well-being than those who follow rigid rules.

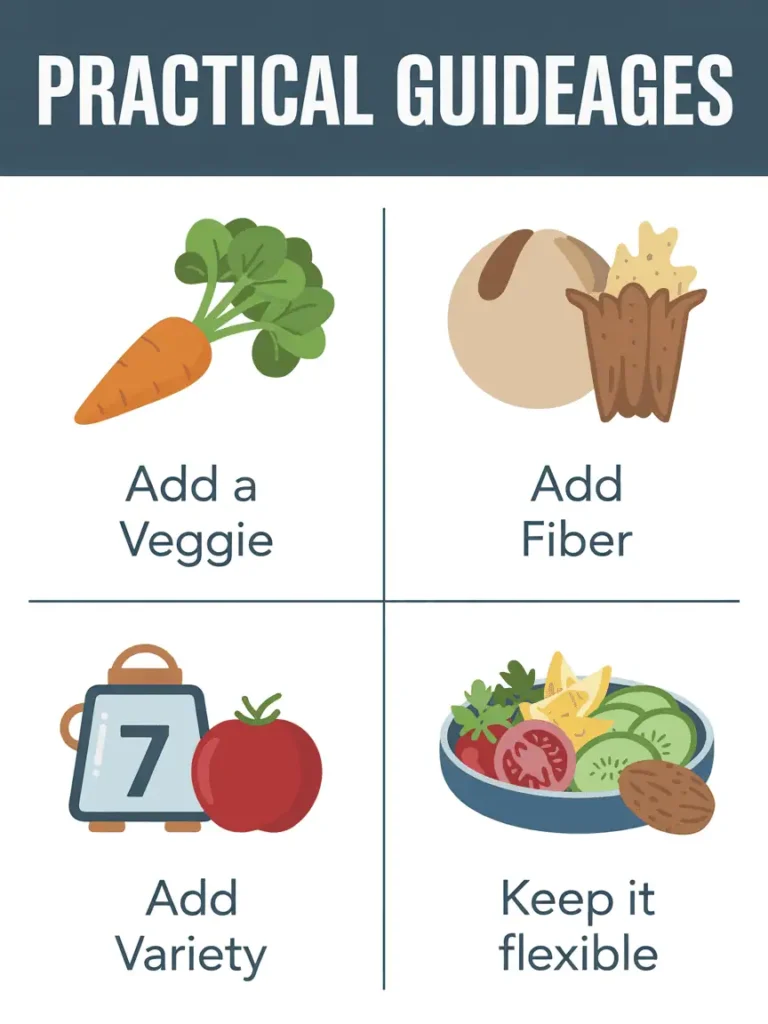

Practical Guidelines That Actually Help

Instead of trying to follow arbitrary “clean eating” rules, here are some evidence-based guidelines that can actually improve your health without making you crazy.

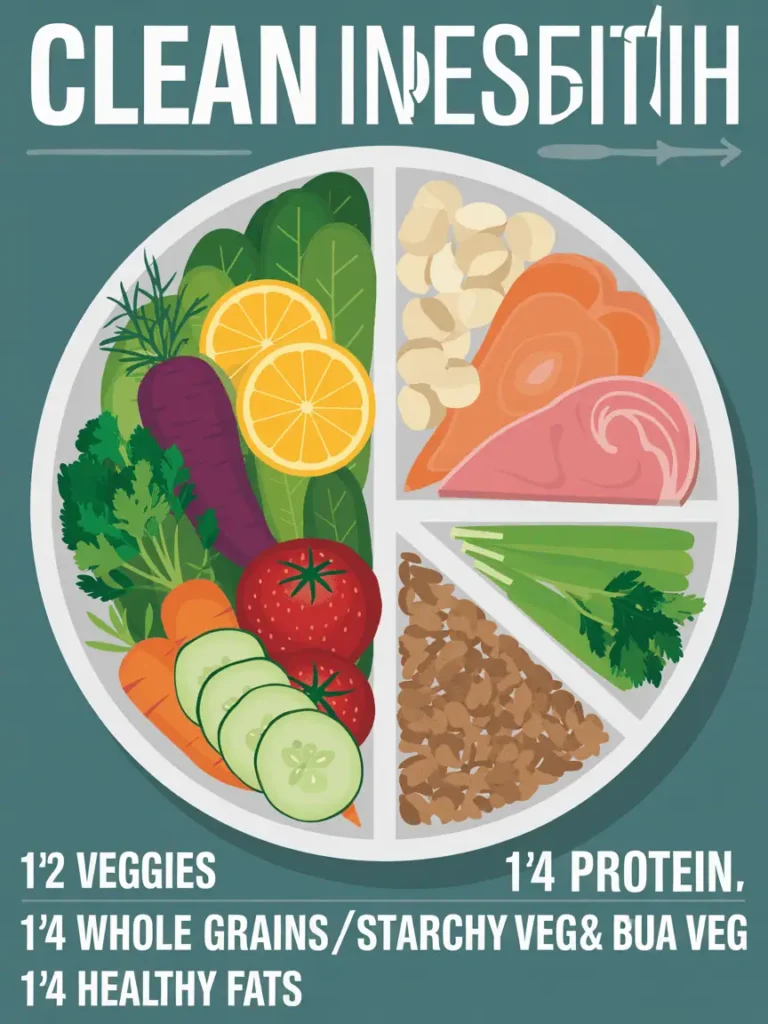

The Simple Plate Method

This is what registered dietitians actually recommend, and it’s way easier than memorizing lists of “clean” and “dirty” foods:

- Half your plate: Vegetables and fruits

- Quarter of your plate: Protein (any kind—meat, beans, eggs, tofu)

- Quarter of your plate: Grains or starchy vegetables (preferably whole grains)

- A little healthy fat: Olive oil, nuts, avocado, etc.

Why this works: It automatically balances your nutrients without requiring you to count anything or avoid entire food groups.

The Addition Approach

Instead of focusing on what to eliminate, focus on what to add:

- Add a vegetable to meals where you don’t usually have one. Spinach in your scrambled eggs, carrots in your pasta sauce, cucumber in your sandwich.

- Add fiber where you can. Choose whole grain bread when you’re buying bread anyway. Add beans to your salad or soup.

- Add variety. Try a new fruit, vegetable, or whole grain each week.

The psychology: This approach feels positive and empowering instead of restrictive and guilt-inducing.

The 90/10 Rule for Ingredients

Here’s a practical way to think about processed foods: If you can identify what 90% of the ingredients are, it’s probably fine. A whole grain bread with wheat flour, water, yeast, salt, and a few other recognizable ingredients? That’s different from a product with 30 ingredients you can’t pronounce.

Real-world application: This helps you distinguish between minimally processed foods (like whole grain bread or canned beans) and ultra-processed foods (like certain snack foods or frozen meals) without getting obsessive about it.

The Mental Health Side Nobody Talks About

One of the biggest problems with clean eating culture is how it affects your relationship with food and your mental health.

The Morality Problem

When you label foods as “clean” or “dirty,” you’re assigning moral value to eating choices. This can lead to feeling virtuous when you eat “clean” foods and guilty or ashamed when you eat “dirty” ones.

Why this matters: Food guilt and shame are associated with disordered eating patterns and can actually make it harder to maintain healthy habits long-term.

A better approach: Think of foods as more nutritious or less nutritious, rather than good or bad. A apple is more nutritious than a cookie, but eating a cookie occasionally doesn’t make you a bad person or derail your health.

The Social Cost

Strict clean eating rules can make social situations stressful. You might avoid restaurants, decline invitations, or feel anxious about eating foods that don’t meet your “clean” standards.

The research: Studies show that people with very rigid food rules often experience social isolation and increased anxiety around eating.

Finding balance: It’s possible to prioritize nutritious foods most of the time while still being flexible enough to enjoy social meals and special occasions without stress.

What to Do Instead

So if clean eating isn’t the answer, what is? Here’s a practical approach that’s actually based on science and real life.

Focus on Overall Quality, Not Perfection

Aim for: Eating a variety of nutritious foods most of the time, while leaving room for flexibility and enjoyment.

Skip: Trying to eat “perfectly” or following rigid rules about which foods are allowed.

Use the 80/20 Guideline

The idea: Make nutritious choices about 80% of the time, and don’t stress about the other 20%.

What this looks like: Eating plenty of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and lean proteins most days, while also enjoying pizza with friends, having dessert at celebrations, or grabbing takeout when you’re too busy to cook.

Listen to Your Body

Pay attention to: How different foods make you feel. Do you have steady energy? Are you satisfied after meals? Are you enjoying what you’re eating?

Trust: Your body’s signals about hunger, fullness, and satisfaction. These are often more reliable than external rules about what you “should” eat.

Keep It Simple

The basics: Eat a variety of foods, include plenty of plants, don’t stress about perfection.

Skip: Complicated rules, expensive superfoods, or eliminating entire food groups without a medical reason.

The Bottom Line

“Clean eating” sounds appealing because it promises simple answers to complex questions about health and nutrition. But the reality is that good nutrition is both simpler and more flexible than clean eating rules suggest.

What actually matters: Eating a variety of nutritious foods most of the time, staying hydrated, and having a positive relationship with food.

What doesn’t matter as much as you think: Whether your bread has five ingredients or ten, whether your vegetables are organic or conventional, or whether you occasionally eat something that wouldn’t qualify as “clean.”

The real goal: Finding an approach to eating that supports your health, fits your lifestyle, and doesn’t make you stressed or guilty about food choices.

Your new mantra: “Progress, not perfection.” Every nutritious choice you make matters, but no single food or meal will make or break your health. Focus on the big picture, be kind to yourself, and remember that the best eating plan is the one you can actually stick with.

The truth about healthy eating is that it’s way less complicated than the wellness industry wants you to believe. You don’t need special foods, complicated rules, or perfect adherence to some arbitrary standard. You just need to eat a variety of nutritious foods most of the time and enjoy your life—including the food in it.

You’ve got this. And you don’t need to eat “clean” to prove it.